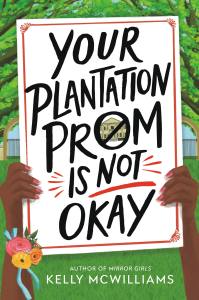

Dear Reader, Love Author: Kelly McWilliams

While I was writing YOUR PLANTATION PROM IS NOT OKAY, Harriet’s wry, sharp voice came flying straight out of my soul—and I think it’s because her journey is so much like mine.

I grew up with a mother who’s an author and professor of African-American Literature. When I was a kid, she wrote historical fiction about tough topics—topics that, in the 90s, no one wanted to touch with a ten-foot pole.

Her second novel was about the Tulsa Race Massacre (then called the Tulsa Race Riot). One day, I was in her office nosing around (almost certainly breaking the rules), when I discovered a pile of disturbing paperwork—photos, reports, and old newspaper clippings, all of them about the bombing of the Black community in Tulsa in 1921. This would form the subject of her second novel, MAGIC CITY, a book for which we’d later visit a courthouse in Tulsa, and witness, in person in the 1990s (!), a modern-day Klan rally.

But let’s focus right now on the paperwork, and the photos of that bombed-out community that shocked the breath out of me as a kid. I rifled through the clippings, the images searing themselves into my brain—and when I got to the bottom of that stack, I found a letter to my mother from my cousin Jerome. He’d written to her from prison.

When I’d ask my mother later about all this, she’d explain the Tulsa Race Massacre to me (Black parents are always having the tough conversations, no matter how old their kids are), and say, of the letter, “Those two things are related, you know. History is why so many Black men are in jail.”

History is why, she said, and it became a mantra for me, a way of coping. When horrible things happen today, I always, always look to history, because the roots of that awfulness are right there. If we only took the time to understand our national history better—to grieve for it, and process it, and take pains not to let its echoes ripple across us like stones on some eternal pond—we wouldn’t see the violence that we do now. And we wouldn’t feel such an enormous weight of pain.

But we don’t do this, of course. Much of American history remains whitewashed and buried.

Did you know, for instance, that though there are over 35,000 museums in the country, only a handful (by my last count: three) focus exclusively on the history of human enslavement?

Did you know that the majority of plantation museums—of which there are hundreds in the South—fail to mention the word slavery at all (instead referring to “workers” and “servants,” which is gravely, offensively inaccurate)?

In this country, plantations—those sites of infinite horror—are still considered by many to be acceptable places to get married, spend a honeymoon, or even throw a prom. This is an erasure that’s violent in nature, and that impacts us even now, in the present day.

Harriet Douglass, the protagonist of my novel, certainly knows her history. She works after school as a tour guide for one of the South’s few enslaved people’s museums, and she lives there, too, with her historian father. When an actress and her influencer daughter buy up the plantation next-door—planning to use it for (you guessed it!) plantation proms, parties, and weddings—she’s consumed by a powerful, constant anger. In 2022, she’s screaming at everyone, as loud as she can, that History is Why!—but it feels, to her, that no one ever listens.

In her lowest moments, Harriet wonders how her mother could bear to stay in the fight as long as she did, and she wonders how she can keep going, shouldering such heavy burdens.

The answer she discovers is three-fold: She can survive through love, work, and humor. By holding her family and friends close (even when they aren’t perfect), and by doing her best to put anti-racist work into the world, and by laughing when she might choose to cry, Harriet charts a course to an activist’s life, learning, most of all, that sometimes you have to lay your burdens down, and trust that you’ve sown the seeds of change, even if they haven’t yet borne fruit.

At the end of the day, you can only keep fighting if you learn to rest.

It took me the entirety of my twenties and a good part of my thirties to learn what Harriet does in this book—how to keep going, when victory seems impossible—and I decided to put it out into the world because so many of us are fighting for something right now. So many of us are struggling, with everything in us, to protect those we love and salvage our world. I dearly hope Harriet’s story resonates, and even comforts, my brave, amazing readers.

Like Harriet, we should all be saying, all the time: History is Why.

But the future is where the real magic is—because that’s still up to us.

Love,

Kelly

Harriet’s world is turned upside down by the arrival of mother and daughter Claudia and Layla Hartwell—who plan to turn the property next door into a wedding venue, and host the offensively antebellum-themed wedding of two Hollywood stars.

Harriet’s fully prepared to hate Layla Hartwell, but it seems that Layla might not be so bad after all—unlike many people, this California influencer is actually interested in Harriet’s point of view. Harriet’s sure she can change the hearts of Layla and her mother, but she underestimates the scale of the challenge…and when her school announces that prom will be held on the plantation, Harriet’s just about had it with this whole racist timeline! Overwhelmed by grief and anger, it’s fair to say she snaps.

Can Harriet use the power of social media to cancel the celebrity wedding and the plantation prom? Will she accept that she’s falling in love with her childhood best friend, who’s unexpectedly returned after years away? Can she deal with the frustrating reality that Americans seem to live in two completely different countries? And through it all, can she and Layla build a bridge between them?